Pink Suit in the Pink Palace: The Discourse of Dress Through Kathleen Wynne’s Portrait

The fashion choices of women parliamentarians are often scrutinized, and as a result, they are often deliberate. This Parliamentary Sketch employs former Ontario Premier Kathleen Wynne’s portrait at Queen’s Park to consider the discourse that surrounds women parliamentarians’ dress.

Annie Dowd

Annie Dowd is a member of the 2024-2025 Ontario Legislative Internship Programme. She served as an editorial intern for the Canadian Parliamentary Review in Autumn 2024.

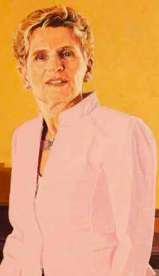

The tour guide extends his arm, gesturing to the portrait behind him. The walls of Queen’s Park are brimming with art, and yet, this is the only portrait in sight that depicts a woman parliamentarian. The portrait is of Ontario’s 25th Premier, Kathleen Wynne. The difference between Wynne’s portrait and the other 24 portraits of past premiers is stark. Among the sea of suits and ties, she stands out in a pastel pink skirt suit.

The tour guide explains that although Wynne did not often wear pink as Premier, the choice to do so for the portrait was intentional. Though, intentionality when it came to fashion was not new to Wynne. As the first and only woman premier in Ontario’s history, it seems deliberate fashion choices were common throughout her political career and, specifically, during her tenure as Premier.

In a discussion with professor of political science and author Dr. Kate Graham, Wynne provided insight into the internal conversations that took place around her style. Wynne explained, “We would have these ridiculous conversations about scarves and colors that I should or should not wear.”1 Concerns were raised about whether scarves would make her “look like [she was] rich.”2

Wynne explained that, from her perspective, the “less popular” she became “the more panicked people were about ‘are you wearing the right makeup? Are you wearing the right clothes? Are you showing up just, right?’”3 These concerns reflect the unique and disproportionate scrutiny often experienced by women parliamentarians and politicians based on their presentation, including their attire.

Conversations concerning gender and dress have emerged historically and contemporarily in various political and parliamentary contexts. More recently, gendered dress codes became a topic of discussion at the British Columbia Legislative Assembly in 2019 amidst the “Right to Bare Arms Movement,” catalyzed by the issue of women members wearing sleeveless tops in the Assembly.4

In an article on the Ontario Legislative Assembly, Kate Korte argues that dress guidelines limit the full accommodation of gender and culturally diverse peoples.5 The study reveals that gender norms and binaries continue to regulate and perpetuate dress codes in political spaces, upholding a correlative perception between gender, presentation, and power.

While Wynne does not sport a scarf in the portrait at Queen’s Park, a floral scarf rests on a chair in the front corner of the painting. The symbolism of this scarf has been dissected by various journalists, including Judith Timson of the Toronto Star, who has described it as “an instant symbol of female political leadership, previously missing at Queen’s Park.”6

Wynne has been transparent about the multi- dimensional reasoning for the scarf’s placement among other symbolic items that personalize the portrait. During her speech at the portrait’s unveiling, Wynne reflected that the scarf is draped over the chair to show that a woman can be premier with or without a scarf, stating simply, “I love scarves. I love the flash of colour. I love the softness.”7

Journalists like Timson also grapple with the paradox of discourses surrounding the fashion of women parliamentarians. While clothing has historically and continues to be employed symbolically and strategically to advance political messages and positions, many people have begun to question whether it should be a subject of focus or conversation.

Does the scarf represent possibility? Does it symbolize the shedding of concern over perception and presentation? Does discussing the symbolism of a scarf in lieu of reflecting on the career of Ontario’s first openly gay, woman premier perpetuate a discourse that demands scrutiny?

As you progress down the hallway of Queen’s Park, the portraits of past premiers depict a gradual transformation in attitude and accepted attire over time. Premiers began to abandon vests in exchange for two-piece suits in the 1960s, and premiers like David Peterson and Bob Rae even shed their suit jackets entirely. Still, Wynne’s portrait stands alone.

Wynne’s portrait offers a unique and tangible avenue to reflect on both women’s representation in parliamentary politics and the gender-specific discussions that continue to surround women parliamentarians. At the unveiling ceremony, Wynne expressed her hope that the portrait would serve as a sign to young people that they can aspire to be premier, regardless of gender. And perhaps, regardless of what they wear.

Notes

1 Kate Graham, No Second Chances: Women and Political Power in Canada, (Second Story Press, May 3, 2022), 220.

2 Ibid.

3 Ibid.

4 Janet Routledge, “‘The Right to Bare Arms’ Drama: Dress Guidelines in British Columbias Legislative Assembly,” Canadian Parliamentary Review no. 4, v. 24 (2020).

5 Kate Korte, “Jackets, Ties, and Comparable Attire: Maintaining Gender Norms Through Legislative Assembly Dress Codes,” Canadian Parliamentary Review, no. 3, v. 45 (2022).

6 Judith Timson, “Power Can Look Like a Scarf on a Chair,” Toronto Star. December 13, 2019 (Page E8) – ProQuest Historical Newspapers: Toronto Star – ProQuest.

7 Kathleen Wynne, “Every Child Has the Right to Aspire to Political Office” (excerpt from the unveiling ceremony speech at Queen’s Park), Toronto Star. December 16, 2019 (Page A10) – ProQuest Historical Newspapers: Toronto Star – ProQuest.